The History of Asian food in America

The history of Asian food in America is long and varied with each cuisine arriving at different times from its own unique journey. Immigrant communities who introduced their foods found success as America’s appetite for adventurous tastes developed with diners embracing more and more niche dishes and flavours. American and Malaysian history share a common thread of intrepid Chinese, Indian, and other southeast Asian peoples choosing to emigrate from their homeland to find prosperity. And just like Malaysia, America’s food culture has been undeniably shaped by cuisines stemming from all over Asia. We look back at the history of how Asian food soared in popularity across the US and what this teaches us about resilience, society, authenticity, and lessons for newcomers wishing to make inroads.

Chinese Food in America

As far as Asian food in the US is concerned, Chinese is by far the most well-known and long-recognised cuisine to serve the American palette. In fact, Chinese cuisine is rated as the most popular ethnic food in America even outstripping Mexican. While the great breadth of flavours in Chinese cooking has a fond relationship with American palettes, it hasn’t always been this way. The road that led to an American embrace of Chinese food started around 173 years ago and was very gradual.

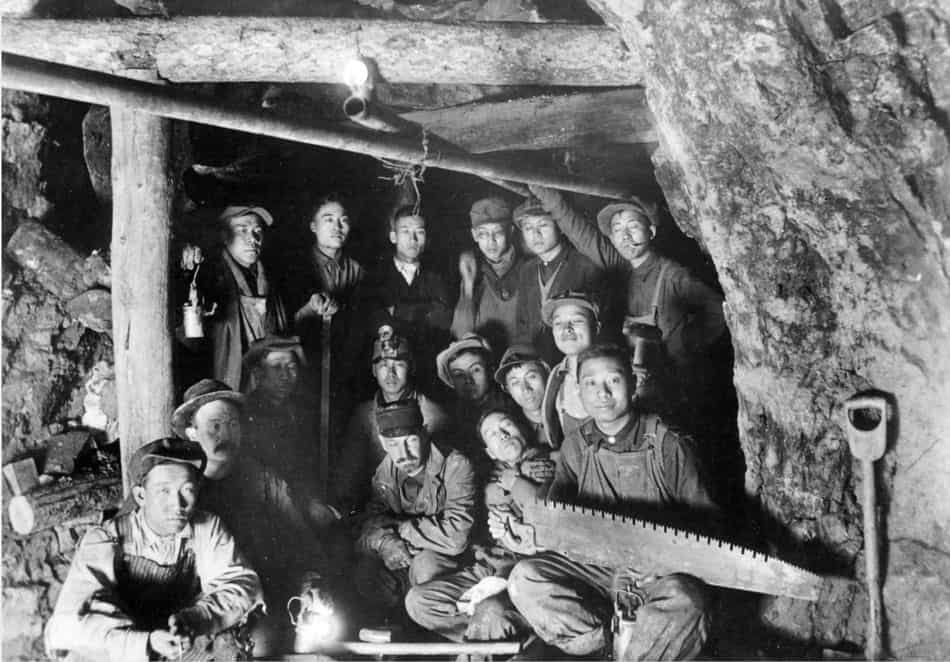

In the mid-18th century, China was reeling from the economic damage caused by conflicts with the United Kingdom. At the same time thousands of miles away on America’s west coast, stories of newly discovered gold in river beds caused a flood of Chinese immigrant labourers who traveled to California in the hope of striking a fortune in the American gold rush. As the gold reserves dwindled, the Chinese immigrants found themselves working as labourers on the railroads, mines and farms.

The First Chinese Restaurants in America

Over time the large numbers of Chinese workers brought culinary traditions as a way of forming a community and retaining their identity. At the time, discrimination was rife and many Chinese were prevented from pursuing most forms of employment. Opening Chinese-style restaurants, therefore, became a viable way to make a living while providing hubs for the Chinese community to relax and socialise. In the early waves of the mid-19th century, immigrants took on manual labour occupations and with a gender ratio of 5:1, it meant that there were not enough women to perform the traditional role of the household cook. As local community hubs, these restaurants allowed Chinese workers access to familiar tasting foods in a friendly environment.

In 1882 a general anti-Chinese sentiment harboured in California resulted in the “Chinese exclusion act” which sought to deny entry to Chinese labourers into America. While this restricted immigration, the act still allowed Chinese merchants to sponsor individuals to immigrate from China if they were to be used for commercial ends. This led to more and more Chinese restaurants being opened on America’s West Coast.

Americans Get Their Taste for Chinese Food

Up until the late 19th century, Chinese restaurants existed to cater mostly to the Chinese community. The prevalent culinary style of the time was derivative of French/European fine cooking – heavy in body and using dairy products, very much the opposite of the Canton style that was served at the time. However, in the late 19th century, many Americans saw an increase in wages and wanted to try more exotic dishes with Chinese being an accessible choice. By this point, Chinese restaurants and businesses had banded together in certain parts of US cities creating the Chinatown phenomenon which added to the spectacle and further enticed America’s culture-hungry middle class.

Adapting to American Tastes

By the 20th century, Chinese food was gaining steady popularity in many cities across the states such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York. Chinese restaurant owners realised the potential of the food they served and started adapting some recipes to suit the American taste buds. Among the many modifications were sweetening some dishes (sweet and sour sauce), including popular vegetables like broccoli, and employing deep frying. The early 20th century up until after the Second world war still saw Chinese discrimination within the employment market so by attracting more non-Chinese patrons to their restaurants, owners could increase profitability. Good examples of adapted dishes include the egg roll which was invented in 1930s New York as a way of making the traditional spring roll more palatable. General Tso’s Chicken is another non-native dish invented in 1950 also in New York as a sweeter take on a Hunanese chicken dish.

Post WW2 and the Spread of Chinese Food

By the late 1960s attitudes had changed and Americans even saw president Nixon embrace Chinese food on his visit to Beijing in 1972. This domestic jolt of confidence and post-war liberalisation of society also coincided with the abolition of the Chinese labour exclusion law seven years earlier in 1965. It meant that well into the 1970s there was a fresh wave of Chinese immigration to the US which brought with it different regional styles of Chinese cooking such as Shadong, Fujian and Szechuan, all offering newer dishes and unexplored flavours. The popularity Chinese food had earned amongst American diners up to this point supercharged interest which led to the influx of more Chinese chefs and resulted in what is deemed today to be the most popular ethnic food in the US with around 45,000 restaurants open nationwide as of 2022.

The long journey from marginalised fringe cuisine to national favourite is likely due to the grinding persistence of Chinese communities, chefs, and restaurants through changing times. It ensured that Chinese food was adequately entrenched in US tastes before new options and delicacies could bolster Chinese cuisine to the huge popularity it enjoys today!

Japanese Food in the US

The prominence of Japanese food like sushi, sashimi, ramen, and teriyaki seems so ingrained in the American gastro leaderboard, it’s even more surprising how quickly this legendary popularity was achieved compared to the long but sure rise of Chinese food. Like all great Asian cuisines, the American love affair with Japanese cuisine starts at the end of the 19th century when Japan set itself the goal of modernising, otherwise known as the Meiji period. Western successes in the way of democratic systems, technological advancement, and national pride were the templates for this modernisation and so Japan sent handfuls of officials abroad to countries like the US where they would watch, learn and report back. In this brief period of cooperation, only those in high society would have exposure to Japanese food which was not available to the masses. This was generally the state up until the Second World War.

Post-Second World War

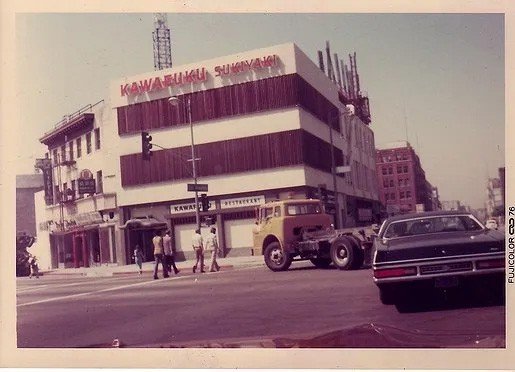

The 1950s did not see much activity when it came to Japanese food popularity in the US and although a very small number of Japanese restaurants did exist, attitudes to Japanese food and culture in 1950s America still remained reserved due to the recent war. It wasn’t until the late 1960’s that this all changed when Japanese businessman Noritoshi Kanai and chef Shigeo Saito opened Kawafuku, America’s first sushi Restaurant in Los Angeles. At the time sushi began to grow popular with adventurous Hollywood stars and those in the entertainment industry which started to bring Japanese food into the national consciousness. Influxes of Japanese businessmen coming to America also increased demand for sushi which was then exposed it to their American colleagues throughout the 70s.

Modifications and Mainstream Success

By the 1980s sushi had become very popular nationwide outside of California with restaurants opening up in most major cities. Prized as a sophisticated dining option, the 1980s saw sushi ascend to the mainstream popularity it still occupies today. The rise was down to three important catalysts at the time:

US-adapted Sushi

As more sushi restaurants opened up, chefs started to once again adapt their food in appearance and ingredients in an attempt to attract more American customers. This gave way to game-changing sushi products such as the California roll which contained avocado, crab, mayonnaise and internally wrapped nori. Other adapted products took the form of the rainbow roll, dragon roll, and Philadelphia roll (a type of makizushi made with cream cheese, smoked salmon, and cucumber). These non-native dishes turned out to be very popular and acted as a gateway for many to gain exposure.

Japanese Culture Goes Mainstream

In the 1980s Japan’s economy was booming and exports of Japanese culture became phenomenally popular in the US. This pop culture explosion saw a fascination with video games, karate, martial arts films, cartoons, karaoke, and of course sushi.

In addition, renewed economic successes in Japan brought a new wave of businessmen to the US who would crave sushi. Similar to the case of Chinese food, native sushi chefs from Japan then emigrated and opened restaurants to feed this emerging US sushi market. The result was more innovations in the type of dishes that were served. This led to the rise of a second wave where non-sushi dishes like Ramen, Teriyaki, and Katsu became more popular as the 1990s progressed.

Sushi in America today

Sushi’s reputation as a healthy cosmopolitan delicacy is no doubt why it remains widespread in the US today. However, the focus on umami, texture, and subtle flavour make sushi and Japanese food in general unique amongst most other Asian foods. Although the concept of raw fish was difficult to grasp for many Americans in the post-war period, sushi and Japanese culture benefited from attitudes becoming more adventurous over time. Interestingly, it would seem that sushi chefs and their expertise were imported to feed the growing domestic curiosity without a large immigrant community from which to springboard.

Korean Food in the US

After many years in the background Korean cuisine has ignited taste buds around the US and is experiencing a boom in the US foodie scene. This sudden popularity did not happen until recently despite Korean migrant communities having been settled in the US for half a century. The story of how Korean cooking became popular in mainstream American starts back in the 1950s. US military involvement in Korea meant that a lot of servicemen were exposed to Korean cooking practices but due to the strong fermented flavours that played on acidity, sourness, sweetness, and spice, it didn’t appeal to a lot of American palettes at the time.

It wasn’t until sometime in the 1970s that economic stagnation caused a wave of emigration from South Korea to the United States. At this point, Japanese and Chinese food was ascending to major popularity partly due to how both communities “Americanised” certain dishes to create mass appeal. This was never the case with Korean food because the Korean community never marketed or adapted their cuisine for American taste buds. Food was used as a means of feeding the community with something that reminded them of home. From the 1970s to 2000 Korean food had fallen beneath the mainstream radar since it remained staunchly traditional and out of reach from what mainstream American food culture was comfortable with. By the millennium the South Korean economy had massively improved which meant less immigration to bolster the already small Korean communities in the US.

Inevitably, the authenticity of many Korean restaurants across the US started getting attention around the same time that Chinese food became more authentic and specialised. Openness to more interesting flavours like Chinese Szechwan meant that people got more curious and adventurous. This allowed Korean food to start gaining fans and popularity in its most authentic form.

Korean-American Fusion

Post-millennium saw the rise of American-Korean fusion food where a number of Korean-American chefs started to incorporate American and Korean ingredients together to create inventive new dishes. The growth of Korean-American fusion started in the west coast street food scene where chefs like Roi Choi used food trucks as a cost-effective alternative to opening a restaurant. Some of the most famous fusion creations include dishes like the bulgogi rice burger, bulgogi beef tacos, and kimchi enchiladas. In the same post-Millenium period the cultural phenomenon of “Hallyu” (the popularity of Korean culture as a whole) started to take off and grow in the US, catapulting Korean-American fusion dining.

Thai Food in the US

Unlike any other ethnic cuisines in America, Thai food didn’t earn its place through generations for perseverance and strategic adaptation, it was down to a state-led marketing effort. By the year 2000, Japanese, Chinese and Korean cuisine was for the most part strongly established in American food culture. After witnessing the resounding success of Asian food in the States, the Thai government had the idea of formally marketing Thai food abroad as a way to generate tourism. Before this happened Thai food had a very small presence in America.

Historically there was a well-established link between America and Thailand since the nation was the US’s main ally in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam conflict. Thailand hosted many military, cultural and educational exchanges with the US, forming a moderate cultural fraternity between the two nations. In the 1950s and 60s, many stationed US servicemen, missionaries, and teachers would return home with the knowledge of Thai cooking but it wasn’t until the abolition of immigration caps in the mid-60s that young Thai restaurateurs would come to the US and set up shop. In the 1980s chefs like Tommy Tang helped bring Thai forward as a fashionable exotic choice on America’s west coast. This once again caught the eyes of movie stars and entertainers. In the early 1970s Thai communities started to import their own products as opposed to relying on Chinese equivalents and defining their cuisine more. This resulted in the opening of LA’s Bangkok Market in 1972, America’s first major Thai supermarket which sadly closed in 2019.

Thai Government “gastrodiplomacy”

In the millennium, the Thai Government sought to use soft power through the way of food to generate tourism and cultural awareness. In the same way that Mcdonald’s was America’s cultural food export to the world, the Thai state wanted to create an equivalent of Thai food. From 1999 onwards the Thai state set up a central training academy where chefs were trained in Thai cooking. Very generous state loans were offered for these chefs to go abroad and set up Thai restaurants where the quality of dishes would be standardised as a way of keeping the Thai taste globally consistent.

The Thai government’s main objective was to make sure their chefs were cooking the most palatable food for their western customers so that the image of Thai food culture had a maximum attraction. Having studied the lessons learned by the Japanese, Korean and Chinese when it came to “Americanising”, the Thai state cooking academies designed dishes that they knew would be most agreeable to a western palette. Pad Thai, coconut soup, and spring rolls are all Thai restaurant mainstays that are hardly ever eaten in Thailand. Regional variations across the north, south, Bangkok, and central Thailand all have their own unique culinary characteristics. However, the food exported to the US is a composite of cherry-picked flavours and textures that were then purposefully adapted. A common observation amongst Thai food experts is the difficulty of finding authentic Thai food in the US.

As of 2022, there are now about 5,000 Thai restaurants in the US up from just 2,000 at the start of the millennium.

Malaysian Food in the US in 2023

It seems like now more than ever Asian food is one of the most popular ethnic cuisines in America with a lot of competition and endless choices for foodies countrywide. In 2023 it might be a crowded marketplace and even though Malaysian culture in the US has a smaller footprint than its contemporaries, this is ultimately irrelevant. If the history of Asian food in the US has taught us one lesson, it’s that people are always after new flavours. Korean cuisine ascended to its current popularity because of a broadening of the American flavour threshold. With travel, globalisation, and interconnectivity, the US has never been more open to trying new tastes. Malaysian food combines regional influences with its own ethnic Malay traditions to create what could be the next major obsession amongst US foodies.

The time is right, and the food is even better, but maybe Malaysian food needs its own cheerleader like Roi Choi or Tommy Tang to spread the word.

Share :